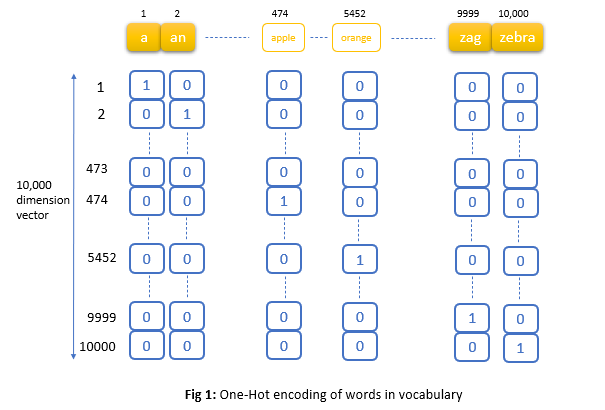

It’s obvious that any deep learning model needs to have some sort of numeric input to work with. In computer vision its not a problem as we have pixel values as inputs but in Natural language processing we have text which is not a numeric input. One common way to convert text to numbers is to use one-hot representation. For example, let’s say we have a 10,000-word vocabulary, so any word can be represented by a vector of length 10,000 with 0’s everywhere except a one ‘1’ in words position in vocabulary.

Problem with One-Hot encoding:

The problem with One-Hot encoding is that the vector will be all zeros except one unique index for each word as shown above in fig 1. Representing words in this way leads to substantial data sparsity and usually means that we may need more data in order to successfully train statistical models.

Apart from the above issue, the main problem is of identifying similar words using one-hot encoding vectors. Let’s see what I mean by this with help of 2 sentences. Examples are from Deep learning specialization - Coursera.

Let’s say we have a trained language model and one of the training examples is I want a glass of orange Juice. This language model can easily predict Juice as the last word by looking at the word orange. Let’s say our language model never seen the word apple before. So, When our language model encounters the sentence I want a glass of apple to predict the next word, it will be able to predict the word Juice if representations for both words orange and apple are similar. But in our case using one-hot representation relation between apple and orange is not any closer(similar) as the relationship between any of the words a or an or zebra etc. It’s because the dot product between any 2 different one-hot vectors is zero. So it doesn’t know that apple and orange are much more similar than let’s say apple and an or apple and king. But the point is apple and orange are fruits and the representations for these should be similar.

So, we want semantically similar words to be mapped to nearby points, thus making the representation carry useful information about the word’s actual meaning. We call this new representation Word Embeddings.

Word Embeddings helps transfer learning:

As we have seen above in the example, even though our training data for language modeling does not have the word apple, if representation for apple is similar to the word orange (both are fruits so we expect most of the characteristics of them are same, so similar representation) then our language model is more probable to predict next word as juice in sentence I want a glass of apple.

How word embeddings look:

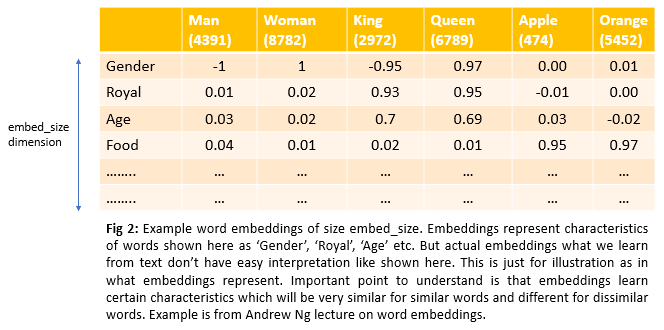

Word embeddings are continuous, vector space representations of words. Word embedding vectors usually have dimensions around 300(in general embed_size). So each word in the vocabulary is represented by a vector of size 300. But what does each value of this vector of embed_size represent? We can think of them as representing certain characteristics like age, food, gender, size, royal, etc. Let’s go through an example to understand this in detail. Even though the below example shows that embeddings are represented by characteristics like age, food, gender, etc., embeddings which we learn won’t have an easy interpretation like component one is age, component two is food, etc., Important point to understand is that embeddings learn certain characteristics which will be very similar for similar words and different for dissimilar words.

If we look at word embeddings of words Apple and orange, they look almost identical. So dot product of these two vectors would be high.

Now that we have a decent understanding of word embeddings, let’s see how we can produce these vectors of embed_size size for every word in the vocabulary.

Generating Word Embeddings:

Below is the architecture we will go through

- Word2Vec Skip-Gram model

Word2Vec Skip-Gram model

The main idea behind the Word2Vec Skip-Gram model is that words that show up in similar context will have similar representation. Context = Words that are likely to appear around them.

Let’s understand this with an example:

1) I play cricket every alternate day

2) Children are playing football across the street

3) Doctor advised me to play tennis every morning.

Above, if we see words cricket, football and tennis all have the word play surrounding them(similar context). So these 3 words will have similar word embedding vectors which are justifiable as these 3 words are names of the sport.

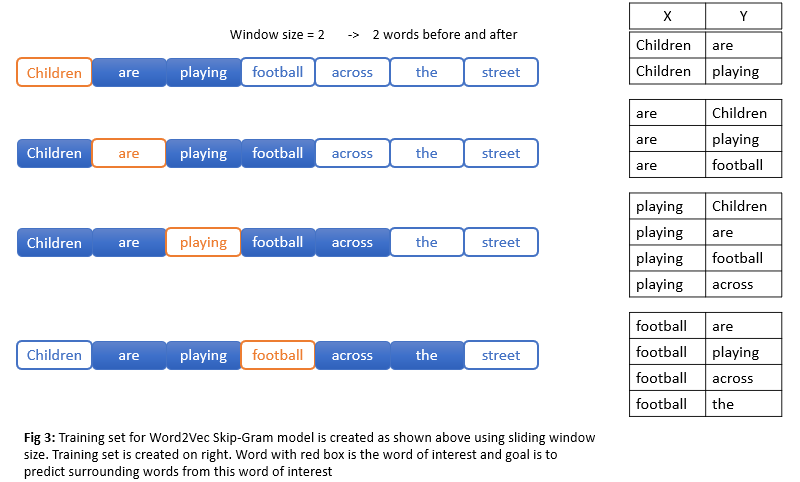

For any word, we can think of context as surrounding words. So our task is to predict a randomly selected surrounding word from the word of interest. Let’s understand this with an example Children are playing football across the street. Let’s pick our word of interest as the word football and playing as the surrounding word. So we give word football to our neural network(which we are going to train and build) and this neural network should predict with high probability the word playing. But context can include surrounding words that come before and also after and not just one word. So authors of paper used window size to select surrounding context words as shown below.

Model architecture:

Below is the model architecture we will be using

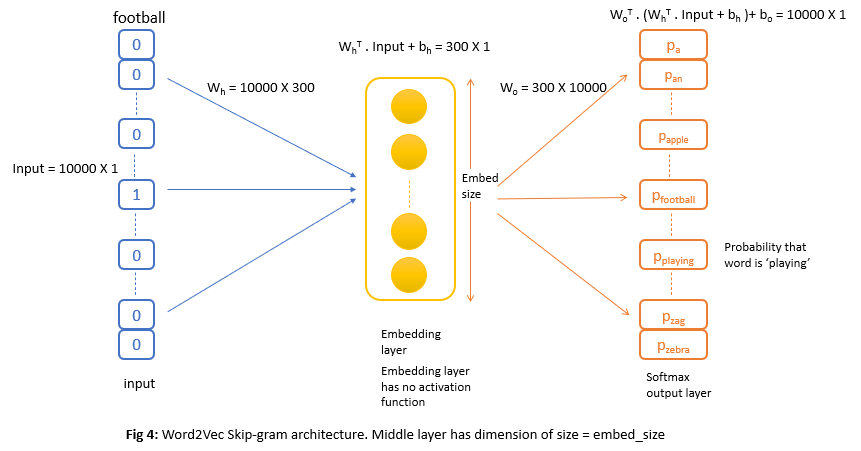

Each training input as shown in fig 3 will be first represented as one-hot vectors that go in to model as shown in fig 4. Then we have an embedding layer with the number of neurons = embed_size(usually this is set to 300) and the output layer will be 10,000 neurons softmax(here vocabulary size = 10,000) that outputs the probability of each word in the vocabulary.

For example, when the word football is sent as input to the trained Word2Vec model above, then the final layer will output high probabilities for the words are, playing, across, the as these are output words for input football in the training set.

Model is trained like any other neural network where we update coefficients using backpropagation and loss function.

Hidden layer

The hidden layer is where all the magic happens. The coefficients of this hidden layer are the actual word embeddings.

For example, let’s say we are learning word embeddings of dimension 300 for every word. Then coefficients or weight matrix of hidden embedding layer will be of size 10000(vocab_size) X 300(embed_size). The output of the hidden layer will be of size 300(embed_size) X 1. This output will pass through the output layer with softmax to generate 10000 values.

Instead of matrix multiplication, as shown above, we can directly use embedding weight matrix as a look-up table. Each row in the embedding weight matrix gives an embedding vector for a word(the result would be the same) in the vocabulary.

Intuition

As we have seen above, the main idea behind the Word2Vec Skip-Gram model is that

Words that show up in similar context will have similar representation

So if two words have similar context(i.e., same words surrounding them) then our model needs to output similar output for these 2 words. For example, in our 3 sentences, the words cricket, football, tennis have similar context as the word playing is the surrounding word. Generally speaking, if we take large text corpora there is a very high chance that these 3 words(cricket, football, tennis) will have playing as a surrounding word. So our model has to output playing as output with a higher probability for these 3 words. This can only happen if embedding vectors for these 3 words are similar because embedding vectors are the ones that go into the output softmax layer as shown in Fig 4.